Coping with change: The influence of early experience, nutrition and stress on behavioral flexibility

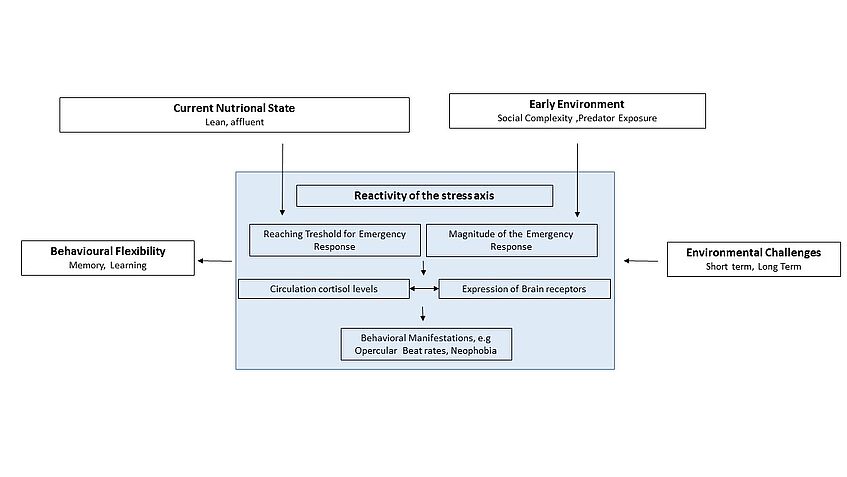

The study of the evolution of behavior is undergoing a revolution with the accelerating awareness that organisms are not only passive agents but play an active role in the adaptive process. Phenotypic plasticity allows an organism to adapt to its environment either through morphological changes or through changes in behavior. Behavioral changes via learning play a special role in phenotypic adaptation because such changes can be reversed, resulting in considerable flexibility. One mechanism that influences several of the components of behavioral flexibility, is physiological stress reactivity. It consists of adaptive neurological and endocrinological mechanisms that prepare an organism to respond to environmental challenges. The physiological reaction to stressful situations provides additional energy for immediate action and enhances attention and memory formation. Thus, it is expected to increase flexibility. However, long lasting disturbance results in chronic activation of the stress axis, which may shift behavioral activation to inhibition and thus impair flexibility. How animals cope with stressful events is to some extent shaped by experiences in early life but also by their current nutritional state. Using a cichlid fish (Neolamprologus pulcher) as model species (see picture ) we will test the influence of early environment, nutritional state, and exposure to long or short-term stressor on behavioural flexibility (see graph). We will use methods from cognitive biology, endocrinology and molecular neurobiology to measure cognitive traits associated with flexibility, the hormonal stress response and gene expression of hormone receptors in the brain. In a world in which animals and humans must adapt to environments that are changing with accelerating speed, understanding the role of stress adaptation to change is highly relevant to both conservation and public health.

Emergency stress responses are advantageous in coping with novel situations and thus should be tightly linked with behavioural flexibility. Both, emergency stress responses and behavioural flexibility, are influenced by a complex interplay between external and internal factors from early life onwards which to date are poorly understood.

Researchers: Sabine Tebbich (Principal Investigator), Leonida Fusani (Co-Principal Investigator), Barbara Taborsky (Co-Principal Investigator), Stefan Fischer, Steve Smith & Virginie Canoine